I’m at the point of Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way where participants fast from reading for a week. So I’ve paused my mid-reads and to-be-reads and I’ve closed all of the hanging browser tabs on my phones and computer. Early yesterday morning I caught myself reaching for a daily devotional book, marveled at the interrupted habit, and left it on the shelf. It felt weird.

Just as not everyone dreams in color or visualizes images when they close their eyes, not everyone hears sounds as they read in their heads. But I’m someone who does hear them. I give words an author-ly narrator: if I’ve heard an author before, that voice is their own, and if not, I invent one for them. I hear them speak their words with that voice, and I track the tone and character of sounds I suppose they transcribed to text as they wrote. I make a full-sense experience out of the flat page and screen. For me, words are the loudest things on Earth. It’s hard not to listen.

So as someone who usually walks around in a word cloud, is writing a book, and is sending you a package of words right now, fasting from reading for an extended period is, plainly, foreign. I voluntarily sit among stacks of books. If I open any one of my inboxes, words spill out like jungle vines searching for water and sunlight. Given the volume of writing that comes my way every day, some through the mail, most through my devices and the internet, not-reading is almost futile. Perhaps even foolish.

The folly of the exercise is why I’m willing to try it. I’m curious how I’ll wrestle with the unrelenting word this week. I’m setting aside the idea that not reading at my usual scale one week requires me to read more next week. I’ll miss things, and some of them will bounce.

It’s also been more than two years since my last silent retreat: rather than repairing to a gorgeous grassy retreat center, this time I’ll be turning down the wordy maelstrom between my ears. I wonder what’ll happen as fewer words pass like sound waves through the air of my mind.

There are many ways to be foolish, and some of them are wise.

One thing I did read before shutting everything down was a speech on the civil rights and social activism of the 1960s from Audre Lorde, poet, author, and activist. Speaking in the 1980s, Lorde looked back and outlined lessons that would’ve been just as insightful and relevant had they been written this year about the activism of the last 25 years. The work she does in this speech—telling a collective story from perspectives often depreciated or missing from common accounts—that is how culture is made. Avoiding storytelling and repressing unusual perspectives is how culture is lost:

“We lose our history so easily, what is not predigested for us by the New York Times, or the Amsterdam News, or Time magazine. Maybe because we do not listen to our poets or to our fools, maybe because we do not listen to our mamas in ourselves.” —Audre Lorde, “Learning from the 60s” (via BlackPast.org)

It’s a simple thing to lose history and culture. First, allow governments and endowed institutions exclusive rights to gate-keep how our stories are taught and told. Then, tell those stories only through formal publishers or platforms and those approved to make for them. Their concerns will shape history. Their art and perspectives will make mainstream culture.

Yet even in the world mainstream taste- and precedent-shapers have made, other lineages exist.

I first learned of the Fool from its shallowest expression. Though my parents had no patience for pranks, English culture taught me of urban April pranksters and mischievous country sprites. I learned to check my school desk for a scare-surprise each April 1, and encouraged my friends to watch out too; I looked sideways and around corners for whichever class clown perched to whip away an unlucky mark’s chair before they could sit; I expected invented news, faked celebrity deaths, and silly lies from any direction. Folly fueled it all: marginal, outlandish, somewhat easy-to-dismiss.

Today, Fool has a muted metaphorical life as the first card in most tarot decks. Fool skips and trips their way into a broad, ordered world. They’re open to adventure, and naive to threat. Amongst other things, they represent the lightness and risk of beginnings.

But in medieval royal courts, folly was a serious job. Fools and jesters both entertained and challenged the nobles they lived with. A fool might flip themselves onto their heads as if flipping tradition itself. They did more than act out innocence of the customary; they were ritually strange, apart from custom.

If others in a court must yield to the Way Things Have Always Been, a Fool’s mandate is to breach Normal.

Flout conventions.

Unmask the expected.

Traffic in surprises.

Tell all the truth, as Dickinson said, but tell it slant.1

Think from different ground.

“Many of the entries that did appear [in the Dictory of Untranslatables: A Philosophical Lexicon] would need to be rethought or unthought if one considered blackness and Black people. If one began from Black, what would an entry on civilization, or claim, or archive or memory or life look like? How would it sound?” —Christina Sharpe, Ordinary Notes, Note 164

How is a democracy that assumes and promotes Black personhood different from democracies built up from enslavement and conquests in ancient Greece and the colonial Americas? How would trade and labor policies paced for the care of elders, children, and disabled people vary from policies based on limited commodities and boundless competition? What could reasoning with the vantage points and communities this society discredits or outright demonizes reveal?

Nothing new under the sun, Octavia Butler wrote in the Parables series, but there are new suns. To reach them, we have to first escape the gravity of this sun, and that requires different first principles and a grounded, playful kind of practice.

“It is important,” Nigerian sociologist Oyèrónké Oyewùmí says, “to know that we have knowledge, that we are worthy, and that, as I always say, we must think and theorize from where we are standing. Unfortunately, too many of us theorize from the perspective of the colonizer, rather than our perspective.”

Oyewùmí connects colonization, language, and perspective in the video below; check it:

Going on Outside

Per WIRED, DOGE has been consolidating information given to once fire-walled government agencies like the IRS, Homeland Security, and Social Security.

From the article: “When you put all of an agency’s data into a central repository that everyone within an agency or even other agencies can access, you end up dramatically increasing the risk that this information will be accessed by people who don’t need it and are using it for improper reasons or repressive goals.”

Two springs ago, I spoke to Wake Forest University School of Divinity about my experience submitting biometric data to the US government over about 15 years, first as a visitor, then as a nonimmigrant student, then a resident, and these days whenever I cross the border. The data net expanded across non-immigrant and immigrant categories in that time, always in the name of national security, and the system checks each new record against previously submitted ones.

Biometric and other kinds of surveillance are almost always pilot-tested before they roll out broadly. These tools are tested on populations that are marginal, disempowered, and under some kind of compulsion, people with no standing to push back.

Facial recognition is common in airport security and boarding lines too now, having first piloted at specific airports (e.g. BWI, DEN, KIN, LHR), airlines (e.g. Delta, United, and Southwest), and flights (e.g. with higher ratios of non-citizen travelers).

Sometimes we’re told we can opt out of these processes, but it’s suspicious to opt out. No digital prints? No trip. Don’t share all your social media info? Must have something to hide. This pattern is not new: We’ve been in this web not just for all of the 21st century but in different ways for the entire life of the United States.

Context for These Times

A few weeks ago,

hosted a nearly 5hr symposium to honor Christina Sharpe (e.g. In the Wake, Ordinary Notes). Like Sharpe’s work, the presentations make for a broad-ranging tour of reflection, expression, and art addressing Black life, death, and futures.View “Living in the Wake” on Wilson’s site. It’s well worth watching slowly, as I did, over two weeks.

Barbara F. Walter has studied the ingredients for civil war, and at TED in 2023 she explained how vulnerable the US is and how we could reduce the risks that those ingredients will drive conflict here.

At the time, Walter’s “how to interrupt” plan included regulating the social media platforms that spread misinformation and thrive on discord. This year, though, social media regulation is off her list because the platforms have already been captured and the new crop of regulators doesn’t really want the responsibility.

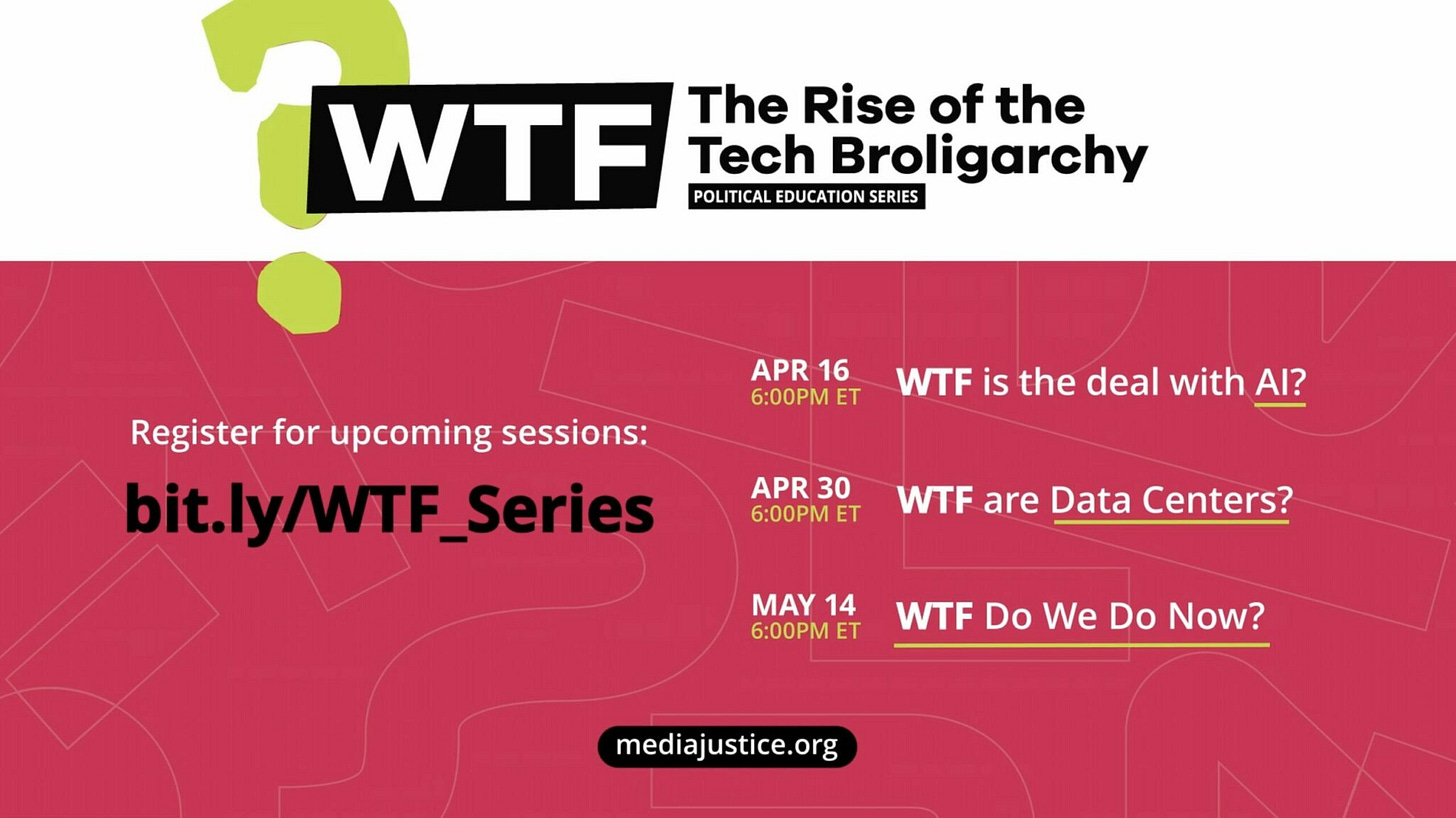

That leaves us with grassroots and corporate pressure. There are tons of historical models for successful economic and stakeholder campaigns, including investor-led anti-apartheid organizing and the Tesla and Target boycotts still happening now. We’ll need more of this coordinated action going forward.Media Justice has been breaking down the ideology and actions of technology leaders who, already very powerful thanks to platforms they own or lead, gained a new level of influence over public policy this year. Bookmark and review the series WTF: The Rise of the Tech Broligarchy on YouTube.

The last live session is on May 14.

That’s all for now.

Try a little folly, and next time we talk, tell me what it taught you.

Take care,

Keisha

I had a sidebar thought here about observational comedians like Bill Burr and Ali Siddiq functioning as another contemporary Fool. What do you think?